The Breadth Alternative to Depth: Rejecting specialization for polymathy

Jan 04, 2025

2025 marks the fifteenth year in my career as a designer. At least to me, that feels like an awfully long time. When I first began my career as a product designer, I had different expectations. I thought that after 15 years, I would be in an incredibly specialized position, honing my skills in some super specific niche. But the truth is I'm far from that. While I can confidently say I've gained significant competence in design compared to where I started, I don't even identify as a designer anymore—despite my experience and engaging in it daily.

However—for the sake of simplifying conversations, business cards, and LinkedIn profiles—I still use the label designer to identify myself externally. In a world where specialization is the most common approach, it's often much easier to label yourself as something you can at least partially identify as than to try and explain yourself without it.

Over the past 15 years of my career as a "designer," I've engaged in a whole host of other disciplines with the intent to ship things that lead to results, straying far from what would traditionally encompass the skillset of a product designer.

Don't call me a generalist

Upon hearing that, most people would be quick to call me the dreaded g-word: generalist. While labeling someone as a generalist isn't always done with negative intent, I feel the word itself has acquired a negative connotation of somehow being inherently suboptimal to the path of career specialization. This in turn can lead those who have intentionally or incidentally chosen to diversify their capabilities to feeling that they are perceived as inferior to their specialist colleagues.

Polymath: An individual whose knowledge spans multiple disciplines, enabling them to solve unique challenges and gain creative insights

While you can still label me as a designer if you like, lately I've come to identify not as a generalist but as a polymath. I believe the term polymath—individuals whose knowledge spans multiple disciplines, enabling them to solve unique challenges and gain creative insights—better captures the nuances without the often negative baggage of the term generalist.

The Rise of Polymathy

The term "polymath" was defined as early as the 16th century to describe individuals who freely engaged in the study of many subjects to expand their minds—something that was still seen as a desirable path at the time. However, at some point, this way of thinking fell out of style and gave way to a culture that valued specialization of skills over diversification. Where does this bias towards specialization come from?

The specialization bias

Modern society seems enamored with the idea that specialization is a necessity, gaslighting us into thinking that it is the only valid path and anything less is falling short. From LinkedIn profiles and job descriptions, to concepts like 10,000 hours to mastery we are constantly exposed to a bias positioning specialization as the preferred path of development.

In education at a young age, we are often exposed to many different concepts from art to music, mathematics, literature, and others as a way to build a foundation. But as we progress through higher levels of education, students are increasingly funneled toward narrowing topic spaces to hone their specialization and prepare them for entry into the workforce where they will continue that path.

Upon entering the workforce, we are swiftly assigned roles in organizations that define our trajectory toward further career specialization—whether as junior software developers destined to become technical architects, or as designers expected to mature in to creative directors—all too often an arbitrary start point seems to lead to a pre-determined destination. With the peak of our specialization often coinciding with the peak of our career, we have become a culture of increasingly siloed expertise.

The dangers of specialization

For all it's praise the specialization approach to career development sets up a dangerous dependency. If we compare career development to the act of investing, specialization would be akin to investing solely in the stock of a single company or industry. When your chosen area of investment is booming, naturally gains will follow. However, there is always a non-zero chance that your chosen specialty could sink in importance or disappear altogether.

For all it's praise the specialization approach to career development sets up a dangerous dependency. If we compare career development to the act of investing, specialization would be akin to investing solely in the stock of a single company or industry. When your chosen area of investment is booming, naturally gains will follow. However, there is always a non-zero chance that your chosen specialty could sink in importance or disappear altogether.

In fact, many of the fears surrounding AI replacing jobs are likely to affect specialists much more than generalists. For individuals who have spent decades honing a narrow set of skills and knowledge, advancements in AI replacing their specialization could result in a "hard-reset" of their career, forcing them to pivot and start from scratch in a new discipline. Contrast that to generalists, where a more diverse skill portfolio reduces the risk of disruption via technology and changes in society.

While there are many advantages to this type of narrow progression that have led us to value it, more often than not we seem to be funneled in this direction without considering the alternatives.

Renaissance Humanism

Interestingly, this emphasis on specialization appears to be a relatively recent phenomenon. If we look back a few centuries, specifically to the Renaissance era of the 14th and 15th centuries, we see a very different perspective. The term "Renaissance man" emerged from this period when attaining competency in a diverse collection of disciplines was celebrated as a symbol of intellectual wealth and status.

Leonardo da Vinci, the most notable example of a Renaissance man, was adept at science, engineering, mathematics, biology, astronomy, and many other disciplines that we often associate with requiring specialization to achieve competency. Through his intellectual diversity, rather than creating discoveries limited to specific fields, Leonardo combined his insights to create new value, enriching his art with anatomically correct figures that were revolutionary for the time and developing many creative yet functional inventions.

Polymathy: The practice of acquiring knowledge and expertise in multiple fields or disciplines, allowing individuals to integrate and apply diverse ideas for creative problem-solving and innovation.

While Leonardo may be the most extraordinary example, Renaissance Humanism—the worldview that defined that era—celebrated the passion for diversity of disciplines as a virtuous form of cultural enrichment for the benefit of both the individual and society. To be studied in a wide breadth of areas allowed polymaths—individuals whose knowledge spans many different subjects—to exchange ideas with a larger audience and combine multiple areas of knowledge to create innovative solutions to complex problems. This breadth of study was not just revered; it was highly encouraged for all who had the opportunity to attain it.

One could easily argue that the average person today has the potential to be far more intellectually wealthy than the aristocrats of the 14th century. The increased accessibility of books and the near-infinite availability of information via the internet have democratized countless learning opportunities. Yet, despite this abundance, why do we so often choose to focus on specialization rather than embrace a more intellectually diverse approach?

The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Specialization

While the Renaissance era marked a conscious embrace of polymathy, the Industrial Revolution signaled a dramatic shift away from this way of thinking, driven by the need for increased efficiency, productivity, and scalability in response to growing populations, expanding markets, and advances in technology. This shift established the foundation for many of the specialization-focused beliefs that exist today.

Before the first major industrial revolution, many goods were created from start to finish by a small group or single individual. Creating a simple garment would require manufacturing yarn, weaving it into cloth, designing the garment, and sewing it—a combination of multiple skills and disciplines to achieve a result. This practice was not limited to textiles; similar multi-skilled approaches were common across various pre-industrial trades, where individuals often took responsibility for multiple stages of the production process. During this era, even a specialized role such as being a garment maker required a relatively diverse set of skills to complete the final product.

Compared to the roles that commonly exist in industrialized societies today, this appears less like specialization and more like a mission-based approach—one where individuals were focused on overseeing and completing an entire project or product from start to finish, rather than performing a narrow, isolated task within a larger system. The mission of the garment maker was to produce a wearable, sellable garment. Contrast that with today, where this process has been broken down into multiple highly specialized roles that can only produce finished products when working in concert with one another.

Productivity Atomism

This shift toward specialization embodied what I would define as "productivity atomism"—a philosophical and educational approach that fragments knowledge into specialized, efficiency-optimized units, prioritizing technical expertise and measurable output over holistic human development and classical learning. This mindset gave rise to concepts such as the factory system and division of labor, which defined the Industrial Revolution. The factory system introduced a more structured approach to production, with the division of labor—separating tasks into individual specializations to increase efficiency—enabling industrialized societies to massively boost productivity.

This shift toward specialization embodied what I would define as "productivity atomism"—a philosophical and educational approach that fragments knowledge into specialized, efficiency-optimized units, prioritizing technical expertise and measurable output over holistic human development and classical learning. This mindset gave rise to concepts such as the factory system and division of labor, which defined the Industrial Revolution. The factory system introduced a more structured approach to production, with the division of labor—separating tasks into individual specializations to increase efficiency—enabling industrialized societies to massively boost productivity.

Fast forward to the present, and despite how much modern startups and tech organizations champion out-of-the-box creative innovation and thinking, our current ways of working and career progression don't seem to differ much from those early production lines. Specialized roles with narrowing progression paths are still optimized for measurable quantitative efficiency and productivity. Of course, there are valid business reasons for this approach. However, as a society, it feels regrettable that we have converged around specialization as if it's the only valid path—often at the expense of cultivating more diverse and adaptable skill sets.

From suboptimal to exponential: The Intellectual compound interest of polymathy

This bias toward specialization, without considering the benefits of alternative approaches, has permeated many areas of modern culture. Even the clichéd phrase used to discount the benefits of generalization itself is contrived to propagate this bias by removing a key part of the quote that emphasizes generalism as a strength:

“Jack of all trades master of none, though oftentimes better than master of one.”

Despite how convinced many people seem to be that specialization is the only virtuous path toward progression, being a generalist is most commonly discouraged by those with little to no understanding of its potential benefits.

The benefits of polymathy

Despite the common bias that generalism is inherently inferior to specialization, the path of a polymath (generalist) carries many distinct benefits.

A common trait among specialized development paths is the tendency to focus on honing knowledge and skills over time, based on pre-defined and known paths of progression. While following this pre-defined path from the fundamentals to advanced techniques is often the most efficient route, it has the side effect of hand-holding specialized practitioners without affording much room for new discoveries and divergence until one has mastered all existing knowledge. In particularly mature disciplines, it’s entirely possible to spend a large portion of a lifetime just catching up on the discoveries of predecessors before beginning to create original insights and innovations.

Innovation through Cross-Pollination

Contrary to specialists, polymaths are able to innovate with new discoveries by "cross-pollinating" their domain-specific knowledge, combining concepts across multiple fields. While the progression paths of domain-specific studies for polymaths mirror those of their specialist peers, the nature of studying multiple disciplines in parallel affords polymaths more opportunities for introspection and original insights.

Enhanced Pattern Recognition

This innovation through cross-pollination can possibly be attributed to an increased ability for pattern recognition. Understanding multiple domains often reveals common principles and frameworks that are effective across fields. Polymaths are not so much creating ideas out of thin air; rather, they are often applying concepts from one seemingly unrelated field to another, creating new discoveries and value.

Imagine how someone with an interest in math might approach musical composition differently from a classically trained specialist. Or how a designer might approach writing a narrative. Leonardo's polymathy led him to illustrate anatomically correct and mathematically perfect representations of the human form. How could polymathy affect your own areas of interest?

Faster Skill Acquisition

Along with pattern recognition comes an enhanced ability to learn new skills. Concepts across differing fields are often similar or shared, allowing polymaths to quickly grasp the fundamentals or complex concepts within a specific domain through their knowledge from other areas. Problem solving approaches used in programming may be applicable to other areas of science and engineering. Likewise, the psychology of influencing human behavior with marketing is similarly effective in the context of design.

What we often consider domain-specific knowledge rarely exists in isolation. The ability to draw connections between seemingly unrelated fields—often dismissed as generalism—actually provides a broader lens through which to view complex problems. These connections can reveal insights that might remain hidden to those working within the confines of a single discipline.

While our education and specialized skills naturally shape how we approach problems, diversifying our knowledge opens up new ways of thinking. By exploring multiple domains, we develop different mental models and frameworks. This variety of perspectives enables us to tackle challenges more creatively and effectively than we could through a single specialized lens.

The challenges of polymathy

Despite the incredible potential of polymathy, it's not without it's challenges.

Despite the incredible potential of polymathy, it's not without it's challenges.

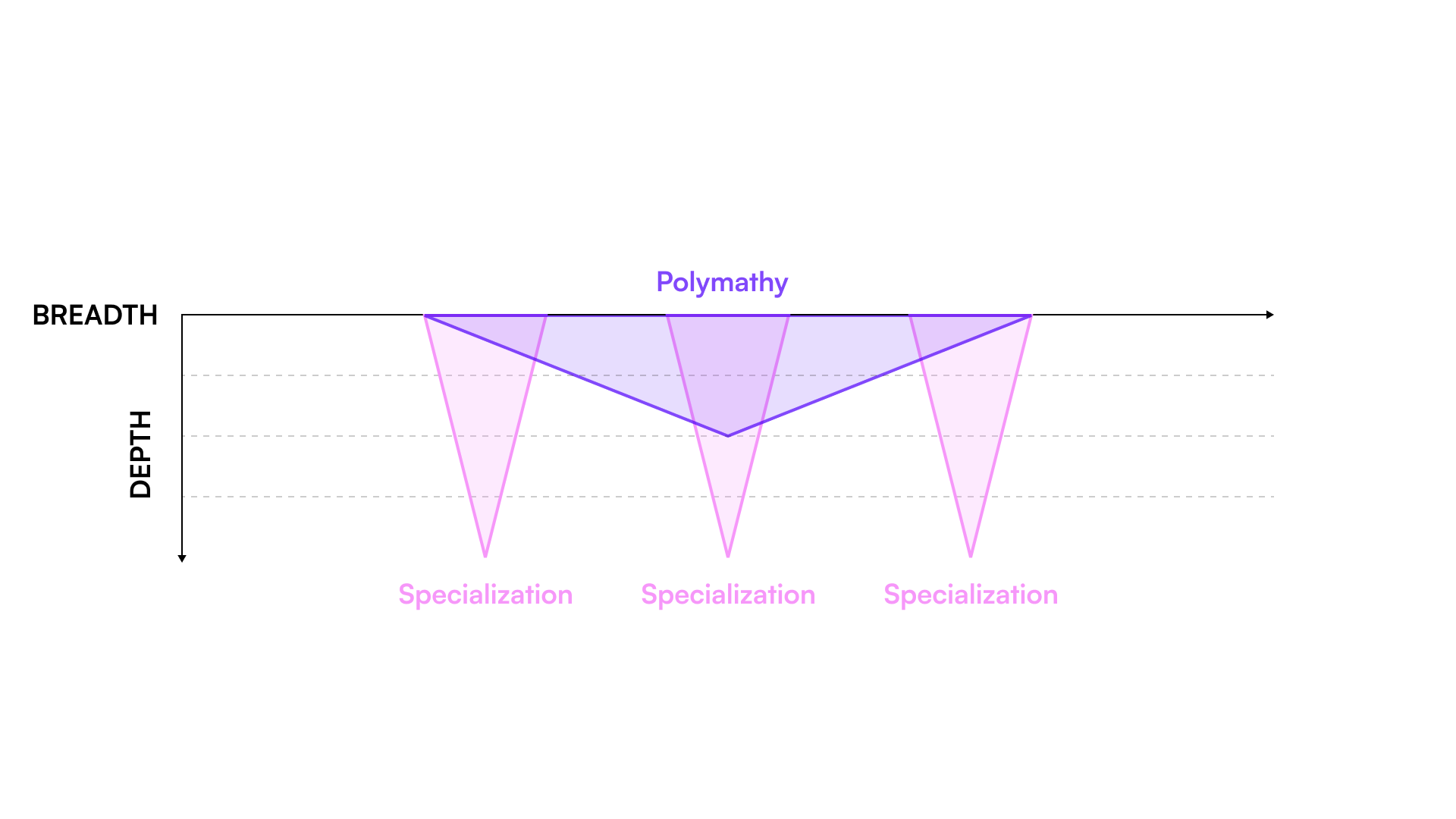

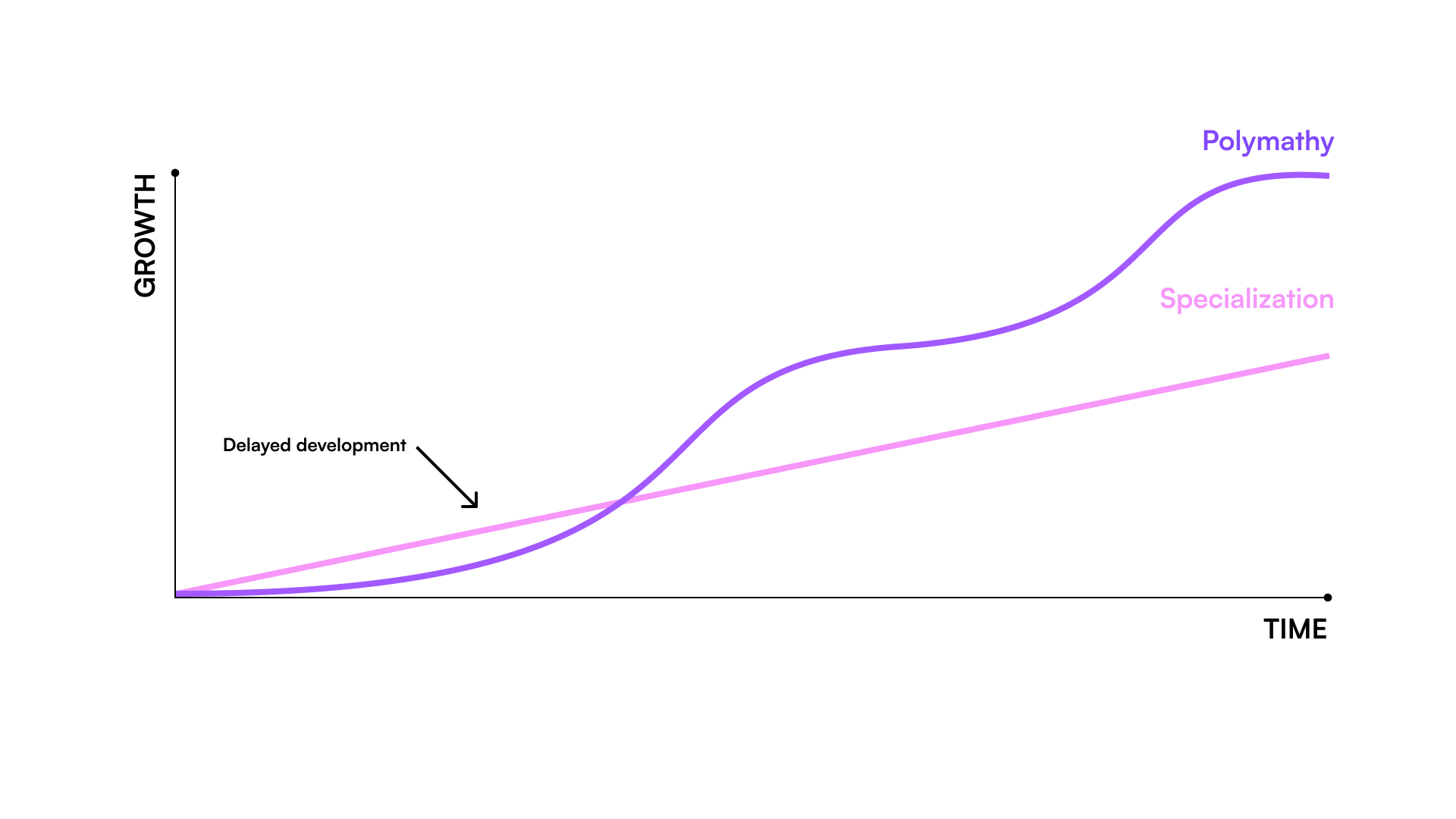

No matter how intelligent you are your development will ultimately be time limited. Given two individuals of similar intelligence and ability—one aiming for specialization and the other polymathy—the individual focused on specialization will likely demonstrate a deeper level of quantifiable expertise at an earlier stage.

While unfortunate, modern society seems to be fixated on the measurement and analysis of quantifiable results early and often when judging the effectiveness of approaches. This is where polymathy falls behind. Starting from zero, the pursuit of multiple disciplines in parallel will show the polymath trailing behind the specialist in every measurable metric, continuing to perpetrate the myth that anything short of specialization is suboptimal.

For someone pursuing polymathy this can be incredibly challenging if you are surrounded by a specialist majority that is constantly discouraging you development decisions.

While it would be difficult to argue that a polymath will ever achieve the same amount of depth in subject as a specialist given equal ability this suboptimal approach can also be seen as a temporary delay in potential exponential growth compared the linear approach of specialization.

As previously mentioned, as polymaths gain competency across multiple domains they will begin to combine those to accelerate the diversity of their knowledge and development overtime. Eventually this breadth can unlock more unique opportunities compared to the specialist career path at the cost of a significant delay in the initial stages of their development.

It's not to say that specialists only have linear growth patterns, they can be exponential too. However for the sake of illustrating the difference, specialists are on a "predictable" linear trajectory because the space they are developing is often largely known and defined. Comparatively, combining multiple disciplines is powerful yet irregular in how it leads to opportunities and innovation. As a polymath increases their breadth or gains deeper understanding of specific topic spaces this growth potential can become more unpredictable.

The relationship of skill diversity leading to unpredictable exponential potential is what I like to call the intellectual compound interest of polymathy.

Embracing your multi-potentiality

So now that you understand that polymathy can be a valid alternative to specialization, how do you get there? Unfortunately I don't think there is a single clear answer here that would work for everyone. Due to the nature of polymathy, every individual likely has a distinct combination of interests that may benefit from being studied in sequence, in parallel or laddered like a polyglot, but my personal advice to you would be to just pursue the areas you have passion in as you discover them. Embrace your multi-passionate self by focusing on what interests you without constantly worrying about how useful a particular discipline will be to you in the future. Without knowledge of a particular subject area how can you determine how much value it will bring to you. If it interests you and makes you happy, don't quantify it, just do it.

Faith

If there's one crucial approach for anyone pursuing polymathy, it's having faith. Early on, it's important not to fixate on quantitative results. Comparing yourself to specialists at this stage will only lead to disappointment. Specialists benefit from predictable results and well-defined competency levels, creating steady feedback loops that make commitment easier. The benefits of polymathy follow a different trajectory—one marked by frequent plateaus, both real and perceived, that can challenge your motivation if you measure yourself against others.

If there's one crucial approach for anyone pursuing polymathy, it's having faith. Early on, it's important not to fixate on quantitative results. Comparing yourself to specialists at this stage will only lead to disappointment. Specialists benefit from predictable results and well-defined competency levels, creating steady feedback loops that make commitment easier. The benefits of polymathy follow a different trajectory—one marked by frequent plateaus, both real and perceived, that can challenge your motivation if you measure yourself against others.

To navigate these plateaus and realize the benefits of polymathy, you need faith: faith that you're progressing toward a breakthrough, faith that you're on the right path, and faith that you'll reach a destination, even if you can't see it yet.

My experience learning Japanese as an adult illustrates this perfectly. Initially, learning basic grammar, vocabulary, and characters showed clear daily progress. But advancing toward real fluency meant hitting plateaus—periods where progress felt invisible. While you might learn basic phrases quickly, having an actual conversation requires exponentially more knowledge and experience. The jump from understanding simple phrases to holding conversations came after what felt like an endless plateau, followed by a sudden breakthrough.

Throughout my journey to Japanese fluency, I often doubted I would succeed. While countless resources describe the benefits of language fluency, you can't truly understand it until you experience it yourself. Like language learning, polymathy can feel like the pursuit of something elusive, without a clear destination until you finally arrive.

This pattern of plateaus and breakthroughs repeated as my fluency grew. The key lesson was learning to trust that my efforts, while not showing immediate results, would eventually lead to breakthroughs. I just needed to keep going, even without knowing when those breakthroughs would come.

This faith is something I've found to be essential in my journey as a multi-passionate person. While it may sound cliché, "trusting the process" is exactly what faith is.

Future-proofing

The question isn't whether polymathy should replace specialization as the optimal path for personal development—both approaches have vital roles to play. While polymaths excel at combining knowledge across fields to generate innovative solutions, specialists remain essential for optimizing individual components with their deep expertise. Each approach brings unique value: polymaths create connections that spark innovation, while specialists refine and perfect the details that make those innovations excel.

The question isn't whether polymathy should replace specialization as the optimal path for personal development—both approaches have vital roles to play. While polymaths excel at combining knowledge across fields to generate innovative solutions, specialists remain essential for optimizing individual components with their deep expertise. Each approach brings unique value: polymaths create connections that spark innovation, while specialists refine and perfect the details that make those innovations excel.

Organizations need both types of thinkers to thrive. Just as polymaths hedge against disruption through their adaptability, organizations must diversify their talent development approaches to build resilience. This means moving beyond rigid career ladders and embracing more flexible paths for growth—ones that accommodate both deep specialization and broad exploration.

As we enter an era where artificial intelligence is increasingly automating the tasks of specialists, the polymath approach offers an alternative path to navigate this uncertainty. The ability to be the conductor of an orchestra of specialization—thinking across domains, recognizing patterns, and combining them to create results—will become even more valuable.