Navigating Feedback: A Strategic Guide for Designers

Jul 15, 2025

The challenge that designers face is that while not everyone is a designer, everyone tends to have thoughts and opinions on how a given design should be. While designers understand that design is more than just visuals, the visual nature of most design opens it up for critique, feedback, and opinions from just about anyone. The reality is that most design stakeholders naturally approach feedback from their own expertise areas rather than design methodology.

This most often results in feedback that is unhelpful at best, and damaging to design work at worst. Have you ever had someone say to you "That's a nice start" or "Let's try something different" or just plain "I don't like this"? These are all examples of feedback focused on subjective feeling and therefore lack the ability to be clarified into clear, actionable feedback.

Or how about the infamous "make the logo bigger" or "change the color to xxx"? These are great examples of feedback in the form of requests or orders which are often due to the speaker being unable to clarify their own intent. Taken as-is, these changes often result in lowering the quality of design rather than raising it. Seemingly simple-looking design is more often than not the result of lots of context and decision-making coming together as a whole. The combination of lack of context and design training can lead to solutions that don't account for the full design context.

The majority of feedback you'll receive as a designer will fall into these two categories:

- Subjective Feedback — Subjective feeling lacking clear logical reasoning

- Prescriptive Feedback — Solution prescribing without a deep understanding of the design, while lacking clarification of intent

So how do we deal with these? Well, you can try to teach everyone to be a great feedback giver, but the onus is ultimately on the designer to improve the feedback process. Let's break down how to approach these common challenges and create conditions for more effective feedback conversations.

Navigating Subjective Feedback—Logic Building

Subjective feedback occurs when stakeholders forego reasoning and instead express purely emotional responses to design work. This may sound blunt, but as a designer, unless the person speaking is part of your target audience, there's limited value in their personal feelings about the design. While influencing emotions through design is important, the most effective feedback during the design process comes from objective, logical discussion rather than subjective feeling-sharing.

The way we navigate subjective feedback is by guiding the conversation back to objective discussion. When stakeholders can't share objective logic behind their input, we can guide the conversation together toward more productive outcomes to help them build that logic through what I call "logic building."

Creating a Point of Reference: Basic Logic Building

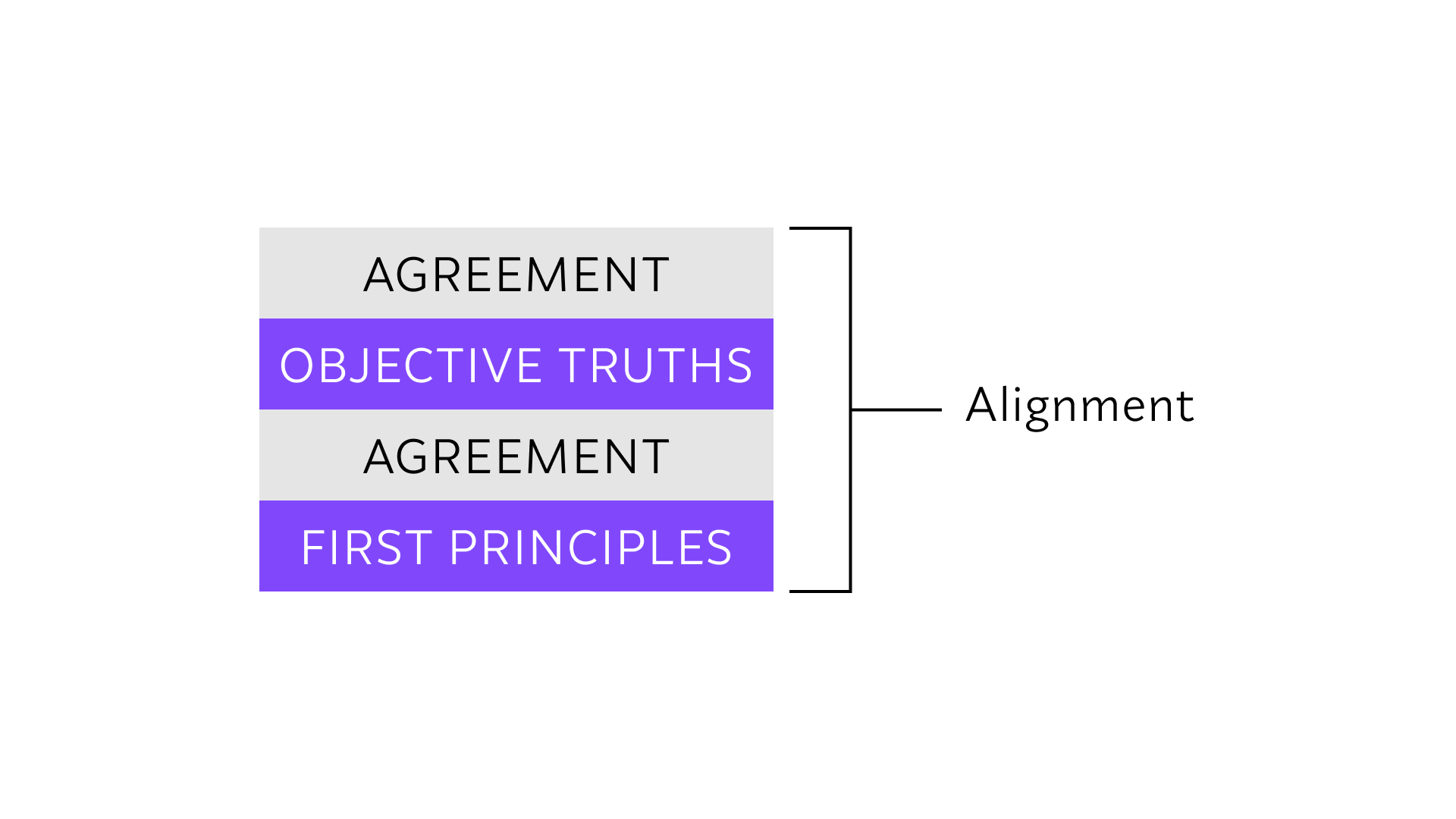

Logic building is the process of progressively building alignment through objective discussion—with the purpose of extracting clear and actionable design feedback. We start by bringing the conversation back to first principles and objective truths.

First Principles are the fundamental, foundational assumptions or facts that serve as the starting point for reasoning. In the context of design and product, these include your target market, chosen business model, unique value proposition, and core user needs. Combined, these act as the compass for your business and product strategy, guiding your team in what they do and why they do it.

Objective Truths are statements or facts that remain true regardless of individual beliefs, opinions, or perspectives. They exist independently of what anyone thinks about them—things like user research findings, business constraints, technical limitations, or market realities.

The reason we bring the conversation back to first principles and objective truths is because these are things everyone should already clearly understand and agree upon.

Shared understanding + Agreement = Alignment

We start from a place of guaranteed alignment and build back up toward the current design conversation. This also frames the discussion with an objective and logical mindset. Participants will be forced to put aside feelings and either agree or disagree with the framing.

Keep in mind you don't always need to go back to the very basics—try to back up the conversation to the nearest reference point where you know all participants will be in agreement. If you find a lack of alignment, bring the conversation back to a more fundamental point of reference.

Example:

"We are building X for [demographic], and our unique value proposition is Y. Our business model is Z, so our objective is to get users to do ABC."

When faced with subjective feedback, consider prompting stakeholders by saying: "I want to understand why you feel this way about the design and clarify how we can address this. Let's take a step back and align on what we are building." Even though you may feel frustrated about receiving subjective feedback, it's important to make your stakeholders feel heard and communicate that we're shifting the conversation to ultimately better implement their feedback.

Attaching Design Logic

Once you've established alignment, you're ready to bring it back to design. To do this, we need to draw a clear connection between the logic we've aligned on (first principles and objective truths) and the design decisions that led to the current design work. This starts by clearly defining the problem you're attempting to solve and then framing specific design decisions to build a logical picture of your solution.

Design logic = Design decisions connected to a clear problem statement

At a minimum, you should have explanations for design decisions covering:

- Why it works this way (functional reasoning)

- Why it looks this way (visual/aesthetic reasoning)

- Similar patterns found in the current product or other relevant products

- Alternative solutions or iterations you considered before arriving at the current proposal

- Limitations or challenges and how they affect the design

Example (Functional):

"Our [target demographic] has [specific challenge], so I designed the feature like this to address those needs" (point to key elements solving the defined challenge)

Example (Visual):

"I used X visual style because it will resonate well with [target demographic]. Through our research, we found that [target demographic] preferred products with these visual elements" (break down elements of visual style, point to other successful examples in the market)

Re-framing the Question

Once you've established alignment and laid out your design logic, re-frame the original concern: "You said you didn't like X and Y. Given what we've discussed about our goals and approach, why doesn't this work for achieving our objectives?"

This shifts the conversation from personal preference to strategic evaluation.

Bringing It All Together

The complete logic building process looks like this:

- Acknowledge the feedback: "I hear that you have concerns about X"

- Establish shared foundation: "Let's align on what we're building and for whom"

- Present design logic: "Here's how my design decisions connect to our objectives"

- Re-frame the question: "Given this context, what specific issues do you see with achieving our goals?"

- Collaborate on solutions: "How can we address these concerns while staying true to our objectives?"

Navigating Prescriptive Feedback

Now let's talk about the second most common type of feedback—prescriptive feedback. To reiterate, prescriptive feedback is when design stakeholders ask for specific changes to design such as "make the button bigger" or "change the color" without clearly articulating their intent or desired outcome. This can be damaging to design when followed to the letter because stakeholders are often looking at a small piece of design in isolation while also lacking a broader understanding of design to prescribe an actually helpful solution.

The Consulting Approach

Despite often being detrimental to design work, prescriptive feedback often comes with positive intent. Stakeholders are trying to help designers by articulating a specific solution, thinking that this is more actionable than ambiguous, subjective feedback. Sometimes it does work, but more often it fails because it reduces a designer's ability to iterate on more effective solutions.

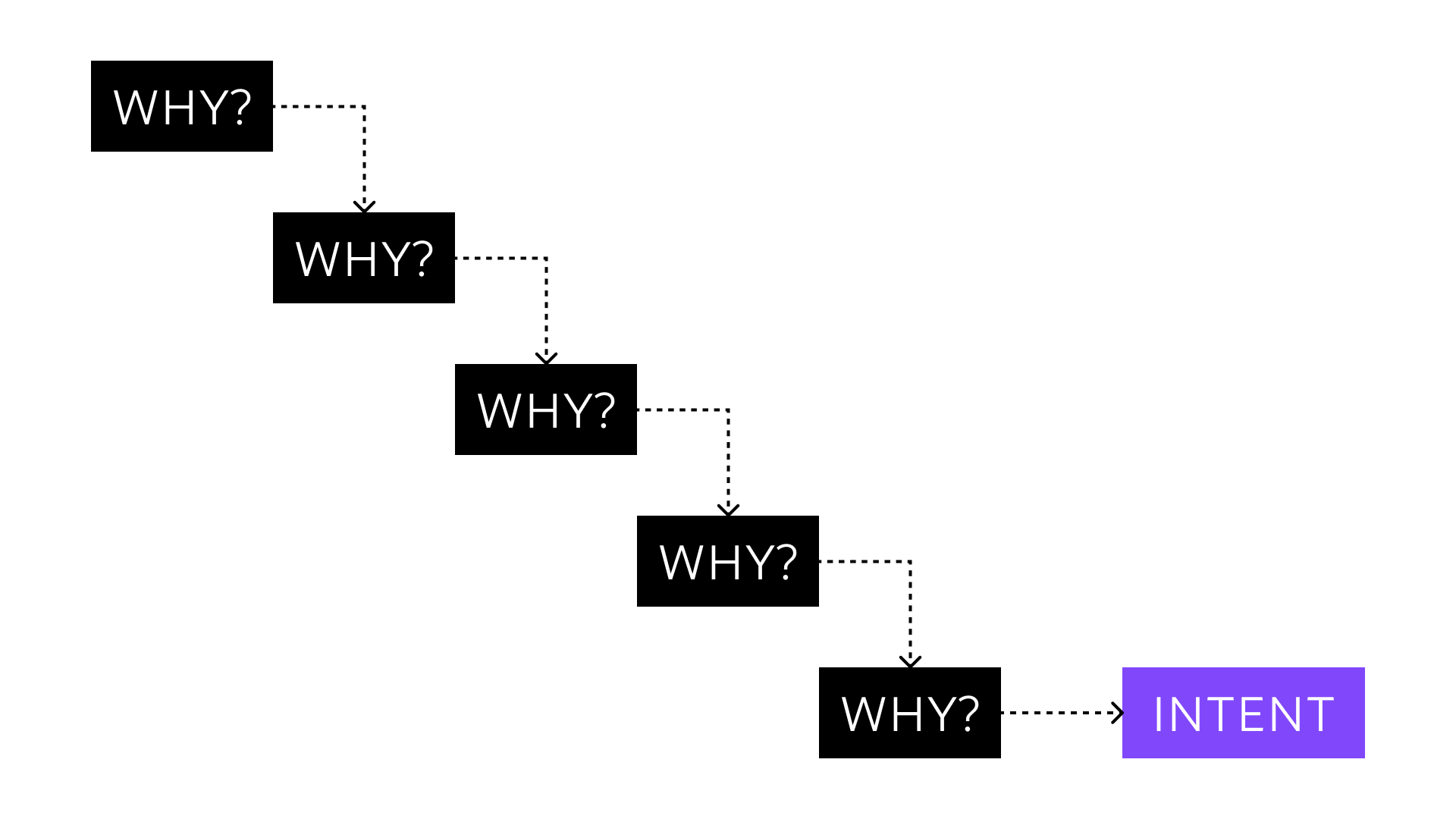

The way we navigate this type of feedback is by using a consulting approach:

- Ask "why" to get more context - We need to understand what they want to achieve and why, rather than following a prescribed design solution as-is

- Get to the root intent - Start by asking why, and listening to the response

- Keep asking "why" - Ask why again, again and again until we get to the root intention behind the feedback

This comes from the "five whys" exercise, famously pioneered by Toyota. However, instead of looking for the root cause of issues, we can also use it to find the root intent of stakeholders giving feedback. Going through this exercise with your stakeholders will more often than not enable them to articulate what their intent is or allow you to express it for them.

How the Five Whys Works in Design Feedback

The technique is simple but powerful: each time you receive a prescriptive solution, ask "why" and listen to the response. Then ask "why" again about their answer. Continue this process until you uncover the underlying business need or user problem they're trying to solve.

Key principles:

- Ask "why" with genuine curiosity, not defensiveness

- Listen actively and summarize what you hear

- Stop when you reach a core business objective or user need

- Usually takes 3-5 iterations to reach the root intent

Example Walkthrough:

Stakeholder: "Make the button bigger"

Designer: "Why do you think it should be bigger?"

Stakeholder: "It's hard to see"

Designer: "Why is it important that it's easy to see?"

Stakeholder: "Because it's the primary action we want users to take"

Designer: "Why is that action so critical right now?"

Stakeholder: "Because that's how users convert, and our conversion rate is below target"

Designer: "Why do you think visibility is the main barrier to conversion?" Stakeholder: "Actually, I'm not sure. I just assumed the button wasn't prominent enough"

Notice how this reveals:

- The real concern: conversion rate performance

- The assumption: visibility is the primary barrier

- The opportunity: to explore multiple solutions for improving conversions

Going through this exercise with your stakeholders will more often than not enable them to articulate what their intent is or allow you to express it for them.

Re-framing on Intent

Once we've drilled down to the root intent of the feedback, we can re-frame on intent. Summarize what the stakeholder's expressed intent is and ask for confirmation of accuracy. If you aren't aligned yet, dive deeper. When you have alignment on intent, the final step is to take responsibility for defining a solution.

Explain to the stakeholder that while their prescribed solution may be valid, there are other approaches that can be taken and you would like to consider those as well. Thank them for helping clarify their intent and explain that you will use that as the foundation for your proposed solutions.

Example:

"So if I understand correctly, you're concerned about our conversion rate and want to ensure the primary action button is prominent enough to drive more conversions. Is that accurate? Great—let me explore several approaches to make this action more prominent and effective, including your suggestion of making it bigger, and I'll present options that address this conversion goal."

If you have design proposals to share at that time, express how those connect back to this newly clarified intent—mirroring what we did with logic building. If you don't feel comfortable proposing new solutions on the spot, circle back with alternatives.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we discussed two approaches to navigating tricky design feedback. However, to be clear, not all feedback needs to be navigated. As a designer, more than anything it's essential to stay humble, listen and address concerns, and be receptive to implementing feedback.

If you are always approaching feedback from the mindset of it being something to be deflected, you're going to quickly sour relations with your various stakeholders while becoming less receptive to actual help and constructive feedback—ultimately leading to worse design and making yourself a worse designer.

Feedback can be scary, but it's something that should be embraced. With the right mindset and a solid framework for navigation, you can leverage feedback to make even better design.